Russia Is the Target of the Harshest Sanctions on Record. Will They Be Enough?

One of the very first recorded examples of a government imposing economic sanctions against another occurred as far back ago as the fifth century BC.

In brief, Athens blocked the city-state of Megara from gaining access to ports and harbors throughout its empire for a number of reasons, including Megarians’ desecration of land sacred to Demeter, the goddess of agriculture.

The blockades succeeded at cutting Megara off from nearly all trade, and its economy tanked as a result.

The sanctions worked so well, though, that they may have backfired on Athens. Many scholars and historians today believe that the Megarian Decree, as the sanctions are called, is at least partially to blame for the Peloponnesian War, a decades-long conflict between democratic Athens and oligarchic Sparta, Megara’s ally.

An important consequence of this war, I should add, is that it marked the end of Athens’ golden age. Upon its defeat, the once-great polis fell under the tyrannical control of Sparta. It never regained its former glory.

Fast forward 2,400 years, and Russia now finds itself the target of some of the toughest and most sweeping economic sanctions ever levied upon a country. Russian banks have been unplugged from SWIFT. The central bank’s foreign assets have been frozen. Yachts have been seized. Mastercard and Visa have blocked all transactions, and crypto exchanges are feeling the pressure to do the same.

Scores of private companies have suspended all operations within Russia. That includes nearly every major international automobile and aircraft manufacturer, from Volkswagen to Toyota to Ford and Boeing. Retailers and consumer tech companies have closed thousands of stores and halted shipments of goods, including Apple, Google, Samsung, Nike, Nestle and more.

I don’t believe the world has ever witnessed such a highly synchronized effort to ostracize a nation and isolate it from global markets. The steps have so far been deep and profound.

And yet will they be enough to stop President Putin? Put another way, how much economic pain is the world willing to bear as a result of the sanctions, when it’s likely uber-wealthy Putin will bear none of it?

The Least Worst Decision

The right answer, of course, is that the economic pain (i.e. inflation) is a very small, temporary price to pay if it means Ukraine has hope for survival. Last week I attended an event hosted by the World Affairs Council of San Antonio, and I was hearted to see incredible support for the Ukrainian people.

Plus, sanctions have long been considered the least worst option, even when the results can be pretty unpleasant for everyone.

Arguably, no American president was as fond of using sanctions to exert influence on the world as Woodrow Wilson. He believed them to be an effective non-violent alternative to war, calling them a “peaceful, silent, deadly remedy… a terrible remedy.”

Although I don’t disagree with President Wilson’s characterization of sanctions, and although they’re far more preferable in most cases to launching an armed conflict, they haven’t always delivered. Athens’ sanctions backfired in the worst possible way, as we saw. Sanctions on Germany, Italy and Japan did little to nothing to prevent World War II.

By the 1990s, President Bill Clinton—who was no stranger to using sanctions himself—regretted that the U.S. had become “sanctions happy.”

And remember, in 2014, the U.S. levied sanctions against Russia for its 2014 annexation of Crimea. Nevertheless, hostilities have raged on in the region and in Eastern Ukraine.

Prepare for Even Hotter Inflation

Writing for the Atlantic Council, economist Hung Tan believes that Russia’s relatively small GDP—it contributes less than 2% to the world economy—means that any global economic pain should be temporary, “even though the fallout of the invasion will define geopolitics for years.”

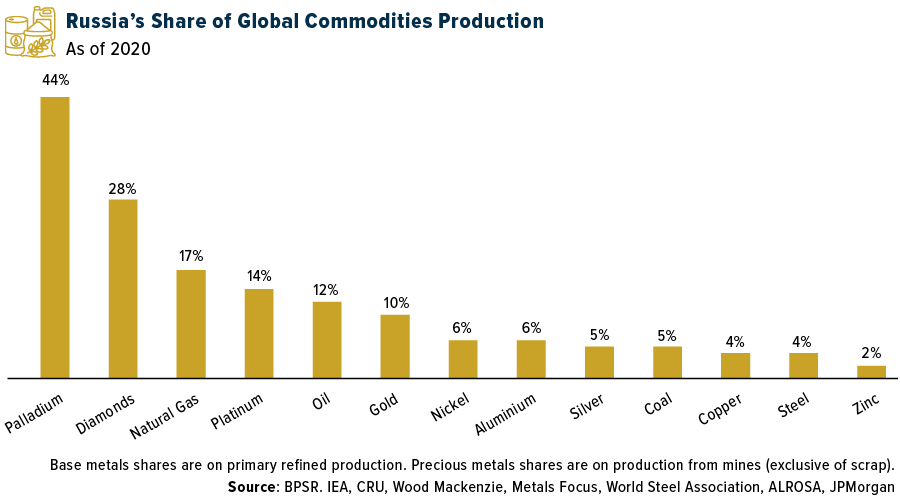

At the same time, ours is very much a global economy. Russia, as many are aware, is a major supplier of oil and natural gas. It’s also believed to account for around 14% of the world’s metals and minerals, with a double-digit share in the production of palladium, diamonds, platinum and gold.

Indeed, the world was feeling the effects of higher energy prices even before Russia invaded Ukraine. Brent crude oil, the global benchmark, briefly crossed above $130 per barrel on Monday for the first time since 2008.

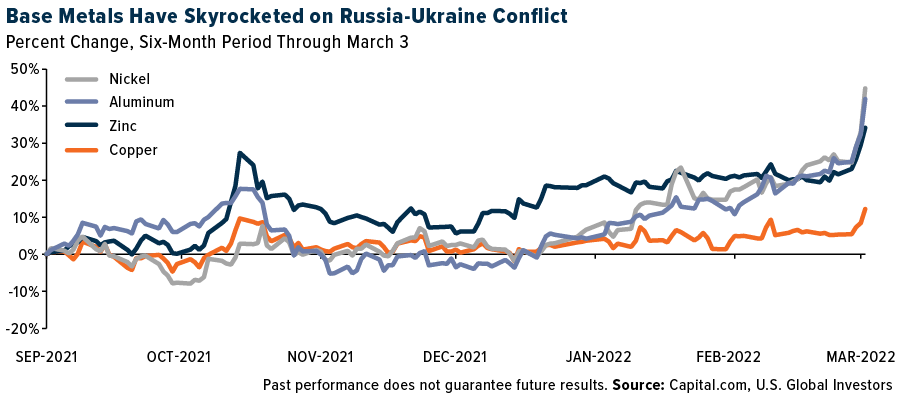

Prices of key base metals have also surged on supply disruptions. The Bloomberg Industrial Metals Subindex had its best week on record, with aluminum, copper and nickel all hitting new record highs in London trading.

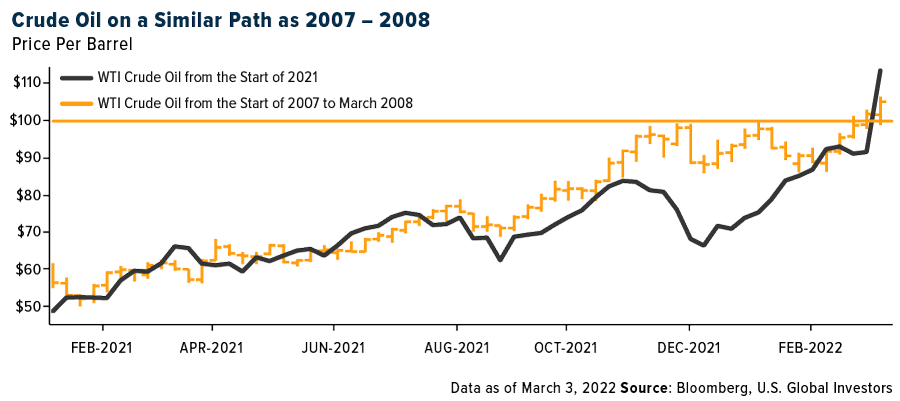

Bloomberg’s Mike McGlone points out that the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude, the U.S. benchmark, is following a similar trajectory last seen at the beginning of the global financial crisis. This is notable because the Federal Reserve started easing in 2007 whereas it’s currently getting ready to raise rates, perhaps as soon as this month, to combat inflation; the move could “portend a lose-lose outcome for crude oil and equities,” McGlone writes.

Banning Russian Oil

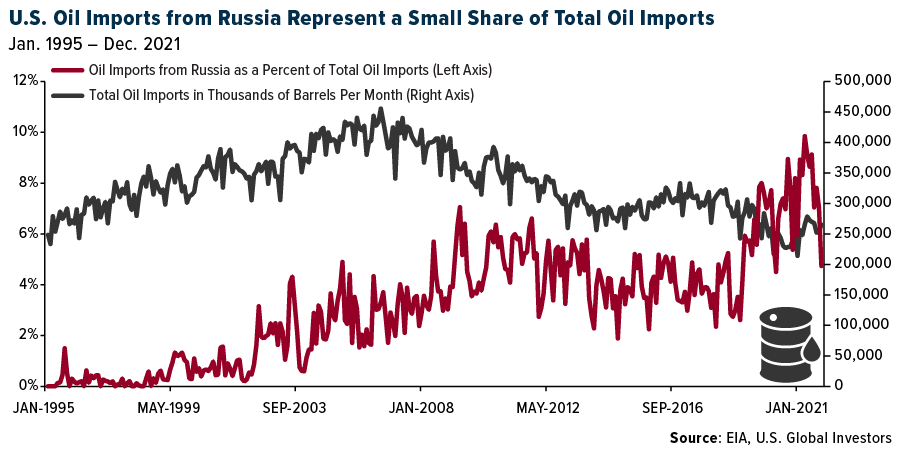

U.S. lawmakers, the White House and Western allies now are calling for imports of Russian oil to be banned. The appetite appears to be bipartisan, and it’s not like the U.S. needs it. Oil brought in from Russia represents a relatively small share (ranging from around 5% to 9%) of the total amount of oil that the U.S. imports from all over the world.

Despite former President Donald Trump’s claim that the U.S. is (or was) “energy independent,” it has imported an average of 277 million barrels of oil and petroleum products every month for the past five years. (The U.S. became a net exporter of refined petroleum in 2020, but the country still imports slightly more crude oil than it exports, as of last month. That could change this year, according to the U.S. Energy and Information Administration (EIA), as the U.S. continues to export a greater and greater amount of the stuff.)

In any case, I think a ban on Russian oil is likely, which could create even more pain at the pump in the short term.

Commodities and Gold

With supply disruptions almost certain to persist, exposure to a basket of commodities as well as gold seems prudent to me right now. Today the price of gold crossed above $2,000 an ounce, its highest level since August 2020, and within throwing distance of its all-time high of $2,073.

As I told Kitco News’ David Lin, I believe gold is highly undervalued. Taking into account excessive money-printing and now geopolitical risk, the yellow metal could easily run up to $2,500 or $3,000.

Watch the interview by clicking here.

All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. By clicking the link(s) above, you will be directed to a third-party website(s). U.S. Global Investors does not endorse all information supplied by this/these website(s) and is not responsible for its/their content.

The Bloomberg Industrial Metals Index is a subindex of the Bloomberg Commodity Index.

Holdings may change daily. Holdings are reported as of the most recent quarter-end. The following securities mentioned in the article were held by one or more accounts managed by U.S. Global Investors as of (12/31/2021): Volkswagen AG, The Boeing Co., Apple Inc.